The fundamental premise investigated on this matter by both titans of Mediaeval history, Gaines Post and Ernst Kantorowicz, was the translatio/transferendo of Roman dignity via Lex Regia, in which Estate dominions could assume a legal character as nations through membership in the communitas regni in a secular sense and the ecclesia universalis in a religious context1. Particularity and a national localism were determined by ius gentium, universal involvement. This is undeniable, but it spoke to a specific development of adaptation to Roman Law. However, gentes, nationes, and populi were regarded as corporate and natural units of political structure prior to this. Post saw the extreme Aristotelian political naturalism which discarded the understanding of propter peccatum of say a Marsiglio of Padua’s Defensor Pacis to have laid the groundwork for “modern statism”2. I would respectfully disagree, I see the similarity as didactic, but it is ultimately disparate, therefore a formal one. I will provide examples beyond this context. Indeed, at the turn of the tenth century, late Carolingian chronicler Regino of Prüm could write of the “diversae nationes populorum inter se discrepant genere, moribus, linguae et leges“3 within Totus Latinitas, itself within the umbrella of the Universal Church as the reason for their various ecclesiastical customs.

Post focused heavily on Spain for incipient nationalism and with good reason. Despite its acculturation to Frankish norms and structures following the Roman liturgical standardisation under Alfonso VI heralded by the inheritance of his realm by his Burgundian sons-in-law, native “Neogoticismo”4 remained a powerful cultural idea for Iberian rulers to invoke in claiming royal authority over Moorish taifas in the peninsula but also in efforts to revive Toledan ceremonial orders and rites and establish ties of kinship and dependency within their regnum. Asturleonese kings had already paid homage to their fallen ancestral homeland in the architectural layout of their new capital of Oviedo, built on the lines of Visigothic Toledo or the assumption of Roman-Gothic title of princeps5. In essence, the proscription of the ancient Visigothic Code; on the crime of treason “against king, land, or folk— adversus regem, gentem vel patriam- resonated in a Castille which emphasised it’s independent jurisdiction from the universal German empire in Central Europe or an aspiring French one just as the Visigothic monarchy of Leovigild had done so with the aid of the Ibero-Roman clergy against the claims of the Eastern Empire. The individual who Post brings to focus the most is the Iberian glossator Vincentius Hispanus. Effectively the process of asserting seperate nationality involved the synonymisation of the oft-referenced Res Publica with the Patria. Hispanus in fact asserts his people’s greatness and individuality by claiming the mantle of rightful Imperium for them and here is directly calling upon the Isidorean tradition of encomium6. This legacy was carried on in the Asturian Chronica Albidense and Alfonsine Chronicles which were both commissioned as continuations of Isidore’s History of the Goths. Both these and Beatus of Liebana’s Commentary on the Apocalypse regard the Gothic Hispani as the chosen people beset by enemies sent by God. 7 Las Navas de Tolosa and the reconquest of Valencia had occurred in Vincentius’s lifetime, so this expugnatio infidelium added glory to Christendom, but it was a glory won by Spaniards. And yet on the other hand, he proclaims the legal independence of the Spanish Kingdoms because of the prohibition under pain of execution of the practice of Roman Law in Iberia8, making them exempt from any form of universal jurisdiction. It is unsurprising that it was in Spanish society that implicit delimitation between who was aboriginal and who was not was the most clear. Of note, the later Purity of Blood discourse hinged on the notion of blood transmission of the noble essence, as nobleza de privilegio became nobleza de sangre in three generations. The discrimination between the Old and New Christians and indeed the caste systems instituted in Iberian posessions across the world were informed by a patrilineal and generational logic.

The Crusading element was fundamental and was no doubt most immediate in Spain, but it left it’s mark across Europe. Kantorowicz noted that the crusading tax pro defensione necessitate Terrae Sanctae was adapted in the 13th century for a tax pro defensione neccesitate regni9. The dire situation of beloved Jerusalem could be applied any dire situation of the beloved homeland. Pro pugna patria. Pro patria mori. The defence of the realm’s peace and the sustenance of the Faith were also combined in Archbishop of Turpin of Reims call to the Franks in the Song of Roland, probably compiled in the 12th century, “for our King we have to die, help to sustain the Christian Faith!…obtaining seats high up in paradise!”10 France was Regnum Benedictum a Deo according to Pope Innocent III11. My Crusader essay should have emphasised the popular conflation of Frankishness and Crusading virtue, but to hammer home the point, I recast again, Guibert of Nogent’s Dei Gesta per Francos(God’s Deeds through the Franks) where the specially chivalric and yet warlike flower of the Frankish race heeded the call of the Apostolic See or William of Malmesbury’s rendition of Pope Urban’s speech where the environment of Francia disposed it’s bellatores to be the finest servants of God’s Will. In reality of course, the heretofore redundancy of the Classical usage of Patria was not because ties to kinship did not exist or were not felt, but rather because modes of auctoritas frequently associated private ownership with right of dominium, just as the Bishop’s ministerium. However within this framework, which lacked a notion of suprema potestas intra iurisdictione, through that of territorial integrity, could an association between corona and patria be established. Afonso II of Portugal won his case before the Papal Court against the partible inheritance of his sister(accepted in Visigothic Law, not so in Salian Frankish Law) by appeal to territorial integrity12. This is because proprietary lordship was also deeply intertwined with custom. And custom implied a community that followed it13.

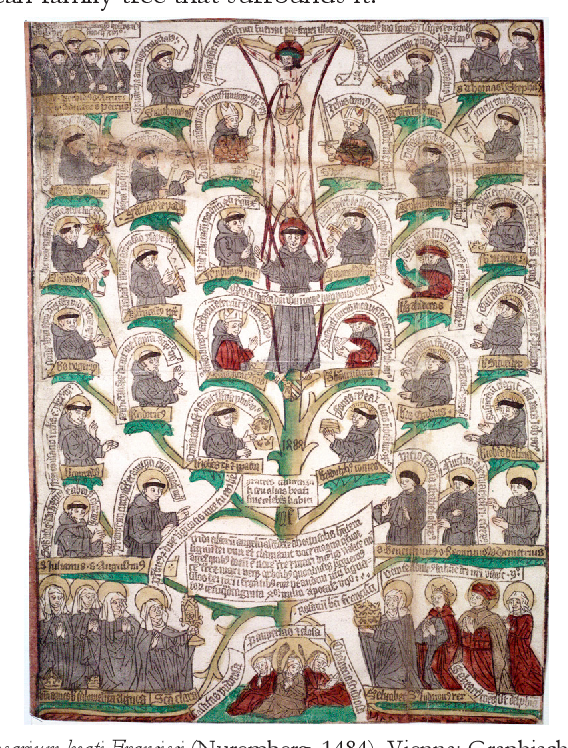

Another important utilisation is of the concept of the angels of nations, or the principatus popularised in the Western Church by Isidore’s Etymologies, but having roots as far back as Victorinus of Pettau’s 3rd century Commentary on the Apocalypse14. The final book from Scripture is pivotal in defining the place of the nations and of their archē in the Providential plan. Despite the negative account of the angelic princes and their nations in the Psalms and the Apocalypse, the conclusion of their role in salvific history, “By its light the nations will walk, and into it the kings of the earth will bring their glory…And into the city will be brought the glory and honor of the nations.“(Revelations 21:24-26), availed the continuity of the nations until the Parousia and furthered the belief that a nation which was consecrated to Christ would bring glory to the Kingdom. Stories of migratory settlement from a distant homeland was a common medieval motif in many a national chronicle, but the place of settlement was seen as a homeland for the peoples to cherish and fulfil a salvific destiny until the Ordained Time, protected by favoured saints of great prestige or local saints with widespread veneration from crafty neighbours and barbaric heathens alike. And piety sustained the people. Patronal associations(feast days, associations, protections etc.) had this effect of strengthening national customs and traditions. Arguably Santiago Matamoros in Iberia serves as the finest example of this. The national mythology of the oriflamme and the rallying of the great vassals of France to the banner of St.Denis were first elevated in writing by the ever dutiful Abbé Suger(the deeds of Louis V, p.127). As per the Abbot, King Louis VI raised the saint’s banner from the altar of the abbey at St.Denis in response to the Kaiser Heinrich V’s threat to surreptitiously attack Reims15. France had no dearth of saints affixed to it and it is visible in the words of one of it’s greatest how imbued and ingrained the love of the Regnum, Dulcissima Francia was, since Joan of Arc proclaimed, “those who wage war against the holy realm of France, wage war against King Jesus himself16”. It should be added that the same Declaration of Arbroath which hailed Robert de Brus as King, also confirmed this in the name of St.Andrew. The adoption of the saint’s Cross, the saltire, later being stipulated by Scottish Parliament in 1385 to be worn by the defending Scotsmen and their serving French auld allies in response to an English invasion. The Declaration is notable for it’s constitutional appeal to the Scottish people through it’s nobles to abrogate the right of the Balliols for the Bruces and also for it’s Israelism where Robert is compared to Joshua and the Scots Gaels to the Israelites conquering Canaan and conquering the Picts.

The Dominican scholar John of Paris or Jean Quidort more than others emphasised in his tractate De Potestate regia et papali that gubernaculum was in accordance with nature. Ethnotypic characterisation was already in vogue, as Hippocratic theories had dispersed through Salernitan medical sources and Isidore’s recapitulation of Roman familism was widely received. But the textual reception of the Ciceronian and Aristotelian corpus catalysed the adoption of a more zoetic notion of political communities. Importantly, this studia humanitas did not involve the dissolution of human predicates until the definition sufficed of one category, no, rather it spurred on the need to distinguish particular characteristics peculiar to each community. The French monarchy played a major role in the development of the notions of the rex est imperator in regno suo17, owing to the continuous rivalry to establish an order of precedence, by which it’s royal house could be proclaimed as the foremost in prestige in Christendom. In praise of Philippe Auguste’s victories, the poet William le Breton uses the term patria nativitas18, and the neccesity of defending it from the ‘rabid Germans’ in his panegyric Philippide19. This same king proclaimed himself Rex Franciae, no longer Rex Francorum, cementing the central attachment of the crown to the nation. The August one’s equally ambitious descendant, Philippe IV, beset by his disputes with the Papacy and the Flemish, not only patronised legistes like John of Paris, Jacques de Révigny, Guilliame Durande and Guillaume Nogaret to produce pro-regnal legal tomes, but also himself spoke of his realm in a strong national sense, writing to the clergy of the bailiwick of Bourges, “ad defensionem natalis patrie pro qua reverenda patrum antiquitas pugnare precepit”20. It is in the massive Speculum Iuris of Durande that you find the explicit warrant for a King to levy taxes pro defensione patriae et coronae21. The dispersion of Quidort’s text and De Regimine Principium of St.Thomas and Tolomeo of Lucca popularised the physiological concept of the body politic. A radical assertion found in this genre was that there was no requirement for a mediatrix from whom authority was naturally derived. The Angelic Doctor’s baptism of Aristotle was an intellectual revolution. In intellectual terms, the moral corpus mysticum was no longer the Church by grace alone, but belong to the secular entity of the political body in toto. At once, John of Paris recognised the fundamental distinction of the two swords(Bernard of Clairvaux’s terminology), but equally he did not render the King wholly separated from the spiritual realm nor the Church wholly spiritual without coercion. Both eschatology and the differing natural environments demanded the multiplicity of naturally independent states. Subjection to the Church and resultant grace perfected the balance of the Kingdom, the highest form of natural society. A handy compromise in contrast to later pro-Imperial Aristotelian polemicists. And it is this intellectual matrix which influenced Dante and Petrarch’s ideas of universal and particular patriotisms(civilitas). The ever adapting rhetoric of the national community was tied to the military-political efforts of the Church and it’s kingdoms to expand their territory.

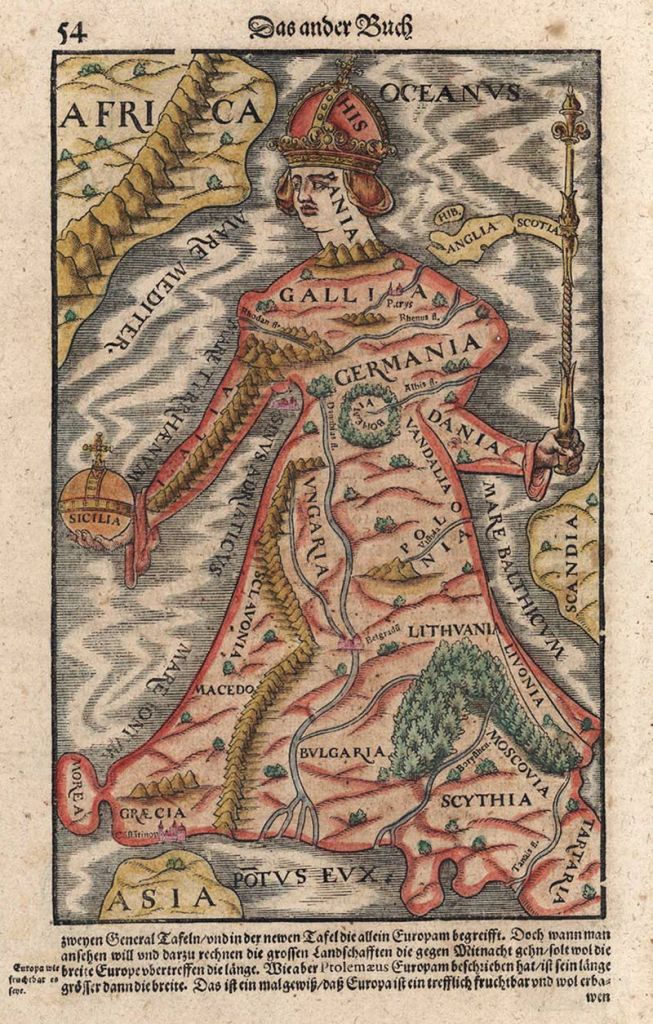

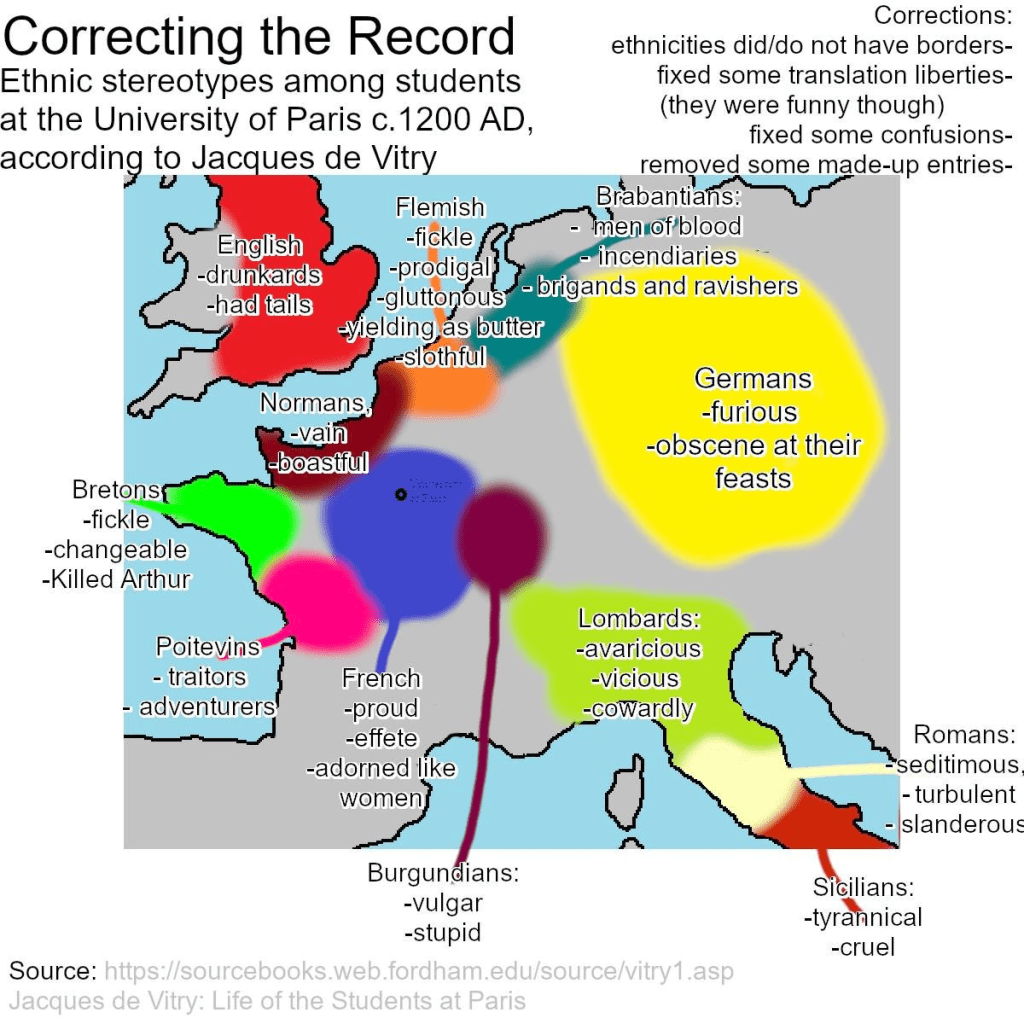

At a basic level, the tertium comparitionis of Christendom existed under which differences of custom and character could be observed. Through a religious prism, the earlier Romans(Eusebius, Orosius), Franks(Gregory, Hincmar), Visigoths(Isidore) and Anglo-Saxons(Bede) considered their gentes to have possessed a special relation to Providence. Note the special role assigned to the Franks in the prologus of the revised Salic Law under Pepin the Short, which positioned the race as the New Israelites, I have also discussed this in my crusader essay. There were oft-repeated origin stories of peoples from an ancestor group or an individual, implausible as they sound now, such as the Franks being Trojans or the burgeoning Swiss being migratory Swedes22. The imagery of patriarchs is evidence in of itself of the familial connotation which is implied, both within a nationality and as part of a brotherhood of nations with common origin. The “great Dane” chronicler Saxo Grammaticus constructed a genealogy in his Gesta Danorum to stress kinship between the English through the Angles and his own Danish folk, presenting the patriarchal brother pair Dan and Angul23. Evocations by saintly authorities include the association of Mosaic familial piety to the defence of the patria by St.Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologia24. Obvious considering that the mechanical clock was invented in Europe, physical location’s alignment with sacred time also factored, the Frankish Benedictine monk St. Rhabanus Maurus divided the world along an East-West Axis in which Persians and Greeks were people of the past, whereas the translation of Empire corresponded to a divine grace and salvific blessing bestowed upon the renewed West25. People differed in their form, through complexion yes, but also by their height, their piety, their capacity for intellect, even to their predilection for the drink. Transmission of Greco-Roman ethnography by Isidore, along with the oral popularity of Biblical stories, popularised the notion that these aforementioned capacities and lived manners(mores) were a product of inhabitation of different latitudes(clima). The Islamic world had it’s parallels, Ibn Khaldun, writing from modern Algeria thought of Syria as posessing the most suitable temperate clime, but thought lowly of the Cushite and Sudani peoples of first and second climes. The great Andalusian, Averroes(Ibn Rushd) also believed his home to be in the best climactic zone, like Greece, producing the “most balanced characters”. This was a form of geographic determinism. St.Albert Magnus’s treatise, De Natura locurum, as can be guessed from the title itself advanced the belief in European learning that natural properties were generated by the physical environment. The great teacher of Aquinas mixed theological commentary with humoral science when he repeated the commonly held belief that Jews had a predilection for haemorrhoids owing to their deicidal curse26. Lack of Jewish military acumen was attributed to their wide dispersion and the curse complementarily by Jacques de Vitry in his Historia Orientalis as well27. The people of this time also adopted the distinction between complexio innata and complexio naturalis, the former is where the phrase, “darkness/blackness of his soul” originates from. This puts into context a sermon by Raoul Ardens, a master of theology at the University of Paris, wherein he tells his audience on the occasion of the Feast of the Holy Trinity that the Jews must overcome their “innate disbelief”, the Poitevins their “innate garrulity” and the French their “innate arrogance”.28 This leads nicely into the genre of ethnic catalogues of vices and virtue, which served to sort physical properties through a topographical framework, an anonymous catalogue from 10th century Spain lists, “the strength of the Goths…the ferocity of the Franks…the rigidity of the Saxons, etc.”29 John of Fordun’s Scotichronicon uses nature as it’s guide, deeming the Normans bears, English foxes, Scots lions etc30. The Planeta of Castilian chancellor, Diego Garcia, was dedicated to the famed Bishop Jimenez de Rada and as part of his effusive praise for this clergyman, Garcia lists virtues associated with all peoples, and further flatters by adding that all these virtues were present in the Bishop31. Biblically, such comparative descriptions are found in the Blessing of Jacob on his deathbed, where Jacob recites the qualities and vices of his sons and in turns those who came from them. The influence of Hippocratic sanguine/humoral theory was evident in the common Crusading perception of the nomadic Turks being bloodless, thereby using Parthian retreat tactics, deemed dishonourable by the Franks who loved a head-on charge. This characterisation is found in Baldric of Dol’s detailing of the Turkish tactics at the Battle of Dorylaeum32. In effect, physical and mental traits were determined by the influence of the climate and the varieties of seasons and a given location, as it was for Aristotle, Hippocrates, Vitruvian and Pliny. Notably, the Mirror of Doctrine by Vincent of Beauvais, patronised by Louis IX, wrote of how the natural complexion reflected mental and physical state33. In French sources, the red-white sanguine was the ideal, with white skin marked by reddish cheeks demonstrating the perfect balance of heat and moisture. Pierre Dubois advised Philippe IV that his children ought to be raised in the climes of Northern France so that they would be fit to lead French armies in the Outremer and develop acute intellects to do so34. Imperial chronicler Otto of Freising, went so far as to state that the Ethiopians could not possibly be resurrected with the ‘affliction of their colour’, as he was no doubt paraphrasing Jeremiah 12:2335. This mirrors the association made between virtue(or lack thereof) and external colour by Dante in the Inferno when he describes the three faces of Satan in mimicry of the Trinity in perfect inversion as privation and alienation, with the left face possessing the black complexion of Ethiopics(where the Nile comes rolling to the plains) representing ignorance. Otto, writing only a century after the Hungarians in Pannonia had converted, wrote of the people as “wild beasts” but described their land as one of many natural charms. He praises Divine Patience in keeping a land so bountiful under a monstrous race for this long and the encouragement for his uncle Frederick Barbarossa to subjugute it by calling back to Charlemagne’s campaign against the Avars is also a nod to the Biblical reference to Canaan as a land of “milk and honey”, Pannonia being ripe for conquest for the new chosen people, the Germans36. Further evident is the idea that land not appropriated to use, in this case by an inferior people did not constitute an order as per lebensrecht, appropriation as efficient cause, rendering no formal cause, an Order or custom governing the land.

Ethnic relation was also not discounted from political claims. This is not an argument for perennial ethnology, which is for another time. But one finds in the faithful Ottonian chronicler, Liutprand of Cremona’s writings an argument for Apulia belonging to Emperor Otto’s patrimony since the gens incola et lingua(race and language) of it’s inhabitants made them part of the Frankish Kingdom of Italy which Otto had won by right, not the Emperor in Constantinople37. The tribal stem duchies(Stammesherzogtümer) under Frankish and later Saxon rule also deserves a mention, as they were clearly political units built on an ethnic basis of local nationalities(Thuringians, Bavarians etc). When battling Rudolf Habsburg, Ottokar II Prêmysl the Golden, called upon the Polish King, Przemysław II, to respond against the German incursion in Bohemia. This appeal speaks of “the consonance of language” but more explicitly the “unity of blood and relation” between the two West Slavic peoples38. This is remarkably similar to the Remonstrance of 1317 by Irish princes which recognised Edward de Brus(brother of Robert) as High King of Ireland, in which the “kingly ties of blood”[between the Gael princes via the House McAilpin] and of language between Greater and Lesser Scotia were invoked39. Quite a quaint connection was also made to Spain, through the fictional genealogy of Milesius being the ancestor of the Irish and Scots, so that in the 17/18th century, Irish wild geese in Spanish service automatically gained the same privileges in Castille as any other subject of the King, per Carlos II’s and Felipe V’s direct decrees. Hugh O’Donnell also claimed to be of “Cantabrian origin” to Felipe II in support of the Spanish Armada. In England itself, you have local magnates appealing to Henry III to expel all Poitevin advisors on the basis of their foreign origin, just as the English kings deliberately excluded local Gaelic clergymen in favour of Englishmen to the position of bishops in Ireland. The prolific William of Malmesbury’s usage gives us more insight into the use of medieval terminology. He speaks of the ambae gentes(both races) of Franks and Anglo-Saxons originating in Germania40. When speaking of the Crusader leader Bohemond of Taranto(whose evocations of both his Frankishness and his Christianity as his gens in Baldric’s Historiae at the Battle of Dorylaeum are referenced in my Crusades article), William speaks of him as Loco Apulus, gente Normannus and elsewhere as Normannicae gentis, of Apulian origin and Norman stock41. In this description you see the consideration of clima and of ethnic pedigree. William even displays the typical notion of the vertical, hierarchical “chain of being” ascribed to medieval metaphysics and in turn, it’s ethnography. There is a Kentish nation(gens Cantuariorum) as there was a Mercian nation(gens Merciorum) and a member of these gens was also equally part of the gens Anglorum42, the same nationality which William the Conqueror excludes from political power43. Jacques de Révigny, a lawyer of Philippe IV mentioned before also speaks of a local Burgundian patria, and then the patria communis of France, to which a greater allegiance is owed in time of crisis44. It would take an essay of it’s own to detail the Alfredian cultivation of national myth of single Anglecynn. Suffice to say that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers to him as ‘king over the whole English people, save that under Danish rule”45 or that his treaty with Guthrum has him claim the right to speak for all English councellors, “Alles Anglecynnes witan”46. A charter dated to 855 freeing from obligation a church in Worcester under the name of Burgred of Mercia already spoke of an Anglecynn in distinction to a foreigner, though it took Alfred’s particular rule(of Anglian Mercia and being rex Saxonum in Wessex) and the vernacular curriculum of Orosius and Bede to accord English history with an inner hermeneutic, gens Anglorum into a true Angelcynn.

Returning to Iberia, by the 16th century we find evidence both at home and in the New World dominions of pre-theoretical scientific concepts such as that of natural kinds and essential properties, foundational to Thomist Aristotelianism being applied interchangeably in context between animal husbandry and generational lineage in men. Quite explicitly, the poetic Cantigas of Alfonso X the Wise written in Old Galician already made distinctions between the Moors as a whole by colour, dividing them into brancos, louros and negros. The 1611 dictionary of Castillian by Covarrubias(Tesoro de lengua Castiliana) emphasises that the tongue in it’s use does not exclude the figurative meaning of relation for sangue47. Again, it remains the case to this day that a breed of dog is termed raza can in the Spanish language. A very popular book on horticulture by Catalan friar Miguel Agustin(Libro de los secretes de agricultura) contains a telling passage, “just as we weigh the variety of complexions in men from different provinces, so we do likewise in agricultural fields”48. In Juan de Mariana’s Historia, we find the following, “just as in crops…the pedigree of men(la raza de los hombres) is transformed due to properties of earth”49. That great pastime of Iberian hidalgueria of horse husbandry inherited from the Arabs also speaks of degeneracion of thoroughbreeds owing to vegetation of regions and breeding with mares of lesser qualities. The term mestizo appears in de Herrera’s Agricultura(1513) to hybrid graft fruit produce and in the La historial medicinal of Monardes there is reference to arboles mestizos(mixed trees). Of older use is the name given to the medieval transhumance sheep herding guild, the Mesta, which comes from Latin mixta, as different breeds commingled in the migration prior to sorting from Old Castille to New Castille. It is very likely that mulatto originates from mule though certainly an older Spanish term from for an illegitimate child, borde, comes from the Latin burdus, a crossbreed between a stallion and an ass. Hence the preponderance of naturalistic language on discussions of official policy and human variation spoke of degrees of mixing, mestizo-cuarterona-ochavona-puchuela-castiza which specified that mixing of the third degree or fourth marked the degeneration of the essence or synonymously deviation or return to pureblood.

The great missionary to Japan, the Jesuit Fr.Alessandro Valignano in his Summario(1583) stated of the Japanese, ‘esta gente es blanca’. This seemed to be part of Valignano’s pitch to his superiors in Rome that Japan could sustain it’s own Catholic institutions, unlike the pedagogical approach taken to the inferior races in Portugal’s sphere of influence. Claiming that it was a province with 67 kingdoms(daimyō fiefs) inhabited by whites who are ‘very discriminating…and very subject to reason’. Here we see a direct understanding of whiteness(woke more correct than mainstream?) as being related to particular virtues exhibited by peoples that was in direct continuity with dominant beliefs in the preceding centuries. Valignano could state confidently that ‘[because] the population of Japan is as white, noble, ingenious, capable of virtue and letters as the people of Europe’ that they could be taught and initiated into his Society. Valignano continued that only the Japanese convert among Asians did so “out of their own will with a desire for salvation”. In fact the Jesuit Order’s 1579 ban on Asians from joining their ranks excluded Japanese, who by 1594 rolls comprised a majority of Jesuits lay members in their own country. Moreso Valignano having been directed for missionary acitvity from Goa commented that Indians possessed a sense of pomp but that they were in manners as ‘wretched and base that they seem like Black people’. Here again we see an insinuation to deprivation of Grace. He even contrasted his life in Japan to his time in India, writing that “he lived with cultivated people, while with base and bestial people”. This opinion was shared by Luís Froís who thought the denizens of Cipangu not only ‘similar in levels in civilisation, but in some aspects even superior’. Humourously, the 18th century French eccentric and imposter George Psalmanazar claimed to be from Japan at times and Formosa(Taiwan) at other times and people in Europe fell for his con. This was centuries before Ehrenarier or the Honorary White designations50.

The new Bourbon king, Felipe V and Pope Clement XI issued decrees and bulls in tandem from 1701-1703 explicating these social castes on the subject of native neophytes to the faith in New Spain51. In 1538, Charles V had offered landowners in New Spain encomiendas in perpetuity if they married Spanish women and desisted in marrying natives. It was the application of these Leyes de Indias and the legal distinctions enforced as the Viceroyalties crystallised which resulted in the creation of a de facto segregated Republic of Spaniards within the territories. Segregation and the establishment of Reductions(reducciones) were justified at times to protect Indians from degradation as well. In France, laws prohibiting marriage were established in the colonies and this was followed in Louis XVI’s own decree prohibiting miscegenetion by contract marriages in 1778. This did not rule out cohabitation and concubinage, restrictions of which proved hard to enforce. Africans, even freedmen in Spanish America, were seen as foreigners and owing to their legal incapacity and their “inferior state” could not attain citizenship to communities. The City Council of Caracas wrote a letter of protest to King Carlos IV in 1796 to protest legislation that would allow for the purchase of citizenship by freedmen. The issue of nativity was also raised by a corporation of Spanish barbers in New Spain in 1635 who complained of the proliferation and competition from Chinese barbers coming via the Philippines, which led to the Real Audienca limiting licenses to foreign barbers in response. It was the case that whenever Spanish, Portuguese or French women were available for marriage, their respective men in the colonies preferred them as spouses, however poor, which explains the shipping of the Órfãs D’El Rei in Brazil and Goa or the Filles du Roi sent to New France. A qualified exception to this was the decree of Afonso de Alburquerque in recently conquered Goa(1510) where a pragmatic miscegenation was permitted between soldier settlers and mulheres alvas[white women], who were daughters of notables of the defeated Bijapuri Sultanate whose ruling class were of Persian origin and it’s administrative class was made up of local Brahmins52. The intention was to create a settler society with ties to the Crown for the purpose of maintaining the Estado da India. It was emphasised here that regeneratio, the new birth of baptism accounted for new privileges and rights. But to what degree was never explicated. The rigidity of the system came into conflict with the resultant heterogenisation and hindered ambitions of naturality among local casados, when their place of birth, even to reinios, those born on the mainland, became an impediment to mobility. A complexity which José I himself tried to resolve in vain via royal decree in 176153. His centralising minister, Pombal had already set the precedent with the Alvará de Lei in 1755 for a license of Portuguese-native marriages in Brazil. This was not a problem dissimilar to the Visigothic canons of the Toledan councils in which Jewry laws continued to applied to those who had converted by which instrinsic affiliations of Jews and their distinctiveness as peoples hindered the political unformity sought by a Kingdom which explicitly maintained it’s legitimacy on Chalcedonian dogma. It was in that city, Toledo, the vital heart of Iberian history that anti-converso laws were first promulgated or resurgent at the start of the 15th century, which was followed by holy and knightly orders over the course of that era. It is important to stress that the communal decree, which was justified as per the IV Toledan Council and King Sisebut’s laws were on carnal basis not spiritual and followed the generational logic as above on the matter of the ex-iudaeos or judaizantes, supported by Canon LX which nevertheless continues to refer to converted Jews as Jews, the same applies to the XII council’s ratification of the laws of King Erwig. The same bone of contention caused the political crisis to boil over in Latin America, where independence factions were militarily and intellectually spearheaded by criollos dissatisfied by neglect in favour of peninsulares. Loyalist Criollos existed too, forming the bulk of the Cuban aristocracy of the 19th century, attaining that sought after prestige in offices in the homeland in Spain’s tumultuous Liberal century. And it is important to point out then that even if later immigration policies of blanquimento/branqueamento by Latin American republics or eugenics in Latin European societies as with all industrialised nations graduated into realms of theoretical science and public health of the body politic in keeping with advancements in neuroanatomy, psychology and cell theory, the linguistic definitions and the terms of discourse(ie. abiding by Catholicity to achieve eugenic goals) had prior antecedents.

A patristic reference which does not speak of genos/gens in a solely religious sense and makes a specific reference to generation and ties of blood comes from St.Cyprian of Carthage’s tenth Treatise, which praises the Divine Eminence of race, that it is more agreeable to have begotten offspring which responds to the parents with like lineaments54. The stereotyping all but natural to men of antiquity and of the medievals is represented by the Church Father Origen writing that the Egyptians were “prone to the degenerate life and slavery to vices”55. It is also well worth expounding on Isidore’s Etymologies, the vehicle of transmission for medieval learning and opinions. It is frankly, a gold mine, like those for which Hispania was famed for in antiquity. In Book IX, he states, “A nation (gens) is a number of people sharing a single origin, or distinguished from another nation (natio) in accordance with its own grouping…from this comes the term gentilitas(shared heritage)56. The word gens is also so called on account of the generations (generatio) of families, that is from begetting(genitus)”. The ‘next of kin’ (proximus) is so called because of closeness (proximitas) of blood. ‘Blood-relatives’ (consanguineus) are so called because they are conceived from one blood (sanguis), that is, from one seed of a father. Stranger (advena), one who ‘comes here’ (advenire) from elsewhere. Foreigner (alienigena), because one is of a ‘foreign nation’ (alienum genus), and not of the nation where one now is…Exile (exul), because one is “outside his native soil” (extra solum suum). Foreigner (peregrinus), one set far from his native country, just as alienigena (‘born in another country’)”57. And of course, “The law of nations concerns the occupation of territory, building, fortification, wars, captivities, enslavements, the right of return, treaties of peace, truces, the pledge not to molest embassies, the prohibition of marriages between different races. And it is called the ‘law of nations’ (ius gentium) because nearly all nations (gentes) use it”58.

The Conciliar nationes are worth a look in themselves. Partly constituted by ecclesial geography and modified by political arrangements, there were still ethnic factors which figured in the politics of Church Councils. Gregory X at Lyons utilised these camps by meeting individually with the nations to get written consent for papal election reforms. At Vienne(1312)59, the final votes of the prelates were called by order of nations. This Council included a Danish and Scottish nation. Constance was famously called by Emperor Sigismund, to heal the Schism within the Church caused by the residency of the Papacy in Avignon. But here we see the flexibility of the nationes blocs, as there was fear of the size of the Italian contingent loyal to John XXIII, and this meant that the Emperor sought to synchronise his party’s votes with the English. No formal union of the parties was established, but the Scandinavian and Bohemian legates joined the German nation, but interestingly enough, bishops from the Imperial francophone regions such as Savoy and Lorraine, on the account of their kinship and shared language, were represented in the French nation60. Recall that the chronicler-chaplain to Raymond of Toulouse during the First Crusade, Raymond of Aguilers, referred to both Northern and Southern Frankish crusaders as part of the Francigenae61. There were genuine criticisms of the national blocs system in favour of a more unitarian collegial model, particularly from Cardinal Pierre D’Ailly, however his importance in France saw the debate devolve into questions of national legitimacy with backing from the French natio. The Anglo-French arguments parsed out that the Conciliar nations represented a general and not a particular nationality, the French side harkening to the four ecclesiastical divisions under Roman obedience of Pope Benedict XII, insisting that the English were under the German division. The English understood that they possessed nationhood with territory equal to that of the French nation, humorously arguing that the representation of the Welsh and Irish delegations magnified this equality62. More clearly, in preparing for the Council of Constance, a Portuguese embassy had resisted the inclusion of prelates from Aragon’s Italian holdings on account of the fact that they were a “truly different nation”63.

TLDR, the medievals were racist.

- Post, G. (2015). Studies in Medieval Legal Thought. Princeton University Press. Particularly Chapter X, Public Law, the State and Nationalism ↩︎

- ibid, Chapter XI, pg.498 ↩︎

- Regino of Prüm, Chronicon, p. XX, note homoaimon, homoglosson,homotropn ↩︎

- Aguirre, M. (2018). La construcción de la realeza astur. Poder, territorio y comunicación en la Alta Edad Media. Ed. Universidad de Cantabria. ↩︎

- Martin, G. (2020). La ‘pérdida y restauración de España’ en la historiografía latina de los siglos VIII y IX. e-Spania, (36). doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/e-spania.34836. ↩︎

- (MUST READ)Wood, J.P. (2012). The politics of identity in Visigoth Spain : religion and power in the histories of Isidore of Seville. Leiden ; Boston: Brill. ↩︎

- J. N. Hillgarth, ‘Historiography in Visigothic Spain’, La storiografia altomedie- vale: 10–16 aprile 1969 ↩︎

- J. Ochoa Sanz, Vincentius Hispanus (1960), ‘quicumque recepit (leges) romanas capite puniatur,’ ↩︎

- Kantorowicz, E.H. (2016). The king’s two bodies : a study in medieval political theology. Pro Patria Mori, pg.166Princeton: Princeton University Press. ↩︎

- “La Chanson de Roland, https://ia601601.us.archive.org/20/items/songofrolandtran00bacouoft/songofrolandtran00bacouoft.pdflines 1128-1135”

↩︎ - “Innocent III, in his decretal Novit: c.13 X 2,1, ed. Friedberg, II,242”

↩︎ - King Alfonso VIII of Castile, Fordham University Press, pp. 80–101, ↩︎

- Thomas Aquinas, The customs of God’s people and the institutions of our ancestors are to be considered as laws…Accordingly, custom has the force of a law, abolishes law, and is the interpreter of law, Summa Theologia, I-II, qu.97 ↩︎

- https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0712.htm “Because to every nation is accorded an angel”. No principality has a status of veneration in the Roman Church save the Guardian Angel of Portugal ↩︎

- Hallam, E.M. (1982). Royal burial and the cult of kingship in France and England, 1060–1330. Journal of Medieval History, 8(4), pp.359–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4181(82)90017-3. ↩︎

- “Jules Quicherat, Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d’Arc (Paris, 1841-49), v,126”, “Tous ceulx qui guerroient au dit saint royaume de France guerroient contre le roy Jhesus”

↩︎ - “The King is an emperor in his kingdom” ↩︎

- William le Breton, Philippide v lines 408–10, in Œuvres de Rigord et de Guillaume le Breton, ed. H.-F. Delaborde, 2 vols. (Paris, 1882–85) ↩︎

- ibid, line 62, xi, line 292, 401 ↩︎

- “Studi in Onore di Gino Luzzatto (Milan, 1949), pg. 289”

↩︎ - “Durandus, Speculum iuris, IV,part.iii,,n.31, includes an argument for the allegiance to the King over a baron, ““vocat eos pro communi bono, scilicet pro defensione patriae et coronae””

↩︎ - Frankish origo story first concoted in the Chronicle of Fredegar. The Swiss stories came into being during a period of upswell of patriotic sentiment in the 15th century from a famous genre of Bernese Illustrated chronicles ↩︎

- Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, Liber I, Caput I . Translated by Elton, Oliver; Powell, Frederick, 2023. ↩︎

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologia., I,qu.60,art.5

↩︎ - Hrabanus Maurus, Commentariorum in Genesim 2, 6, PL 107, col. 513C, in Opera, Corpus Christianorum. Series Latina 72, ed. P. de Lagarde ↩︎

- J. Gebke, (Foreign) Bodies Stigmatizing New Christians in Early Modern Spain, trans. H. W. Schroeder (Vienna, 2020), pp. 110–11 ↩︎

- Jacques de Vitry, Historia orientalis, ed. and trans. J. Donnadieu (Turnhout, 2008), p. 328. ↩︎

- Raoul Ardent, Homilia ii.2, ‘In die Trinitatis’, PL 155, col. 1949C-D ↩︎

- John of Fordun, Scotichronicon cum supplementis et continuatione Walteri Boweri, 2 vols. (Edinburgh, 1752), ii, 126; Walther, ‘Scherz’, no. 153a. ↩︎

- Diego Garcia, Planeta, ed. P. M. Alonso (Madrid, 1943), pp. 177–8: ↩︎

- Titterton, J., ‘Bloodless Turks and Sanguine Crusaders: William of Malmesbury’s Use of Vegetius in His Account of Urban II’s Sermon at Clermont’, The Medieval Chronicle 13 (2020), pgs.289–308 ↩︎

- Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum doctrinale xiii.50 (Baltazar Bellerus, Douai, 1624; reprint Graz, 1965). ↩︎

- Pierre Dubois, De recuperatione terre sancte,University of Chicago Press ed. Diotti, pp. 119. ↩︎

- Alastair Minnis (2015). From Eden to eternity. Creations of paradise in the later Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University Of Pennsylvania Press, pg.154 ↩︎

- Gesta Friderici i.32, ed. Schmale, p. 192. Cf. P. Görlich, Zür Frage des Nationalbewuβtseins in ostdeutschen Quellen des 12. bis 14. Jahrhunderts (Marburg, 1964) ↩︎

- Liutprand of Cremona, Antapodosis, 111.23; Relatio de legatione Constantinopolitana ad Nicephorum Phocam, 1.9,1.37,

1.40. ↩︎ - R.Bartlett, Medieval and Modern Concepts of Race and Ethnicity, Journal of Medieval and Modern Studies, Duke University Press, 2001 ↩︎

- http://www.nootherlaw.com/archive/remonstrance-of-the-irish-princes.html ↩︎

- Descriptions found no.35 above, but originally from William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum, trans.R.Mynors, 1.68, pg98-99 ↩︎

- Ibid,2.134, pgs.212-213 ↩︎

- Ibid. 1.88, pgs.128-129 ↩︎

- Ibid 3.254, pg.470 ↩︎

- Found in no.1, (Chapter VIII, Public Law and the State) From the Commentary on the Institutes of Justinian, Paris MS.Latin, no. 14350, quia Roma est communis patria, sic corona regni est communis patria, quia caput ↩︎

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 886, ed.Bately, 53 “Ilcan geare gesette Ælfred cyning Lundenburg, him all anglecyn to cirde ↩︎

- ‘Alfred-Guthrum treaty; ed. Liebermann, Die Gesetze, I.126-9; transl. in Keynes and Lapidge, Alfred the Great ↩︎

- Sebastián de Covarrubias, Tesoro, 824 ↩︎

- Miguel Agustín, Libro de los secretos de agricultura, casa de campo y pastoril,

facsimile edn (Valladolid, Spain: Editorial Maxtor, 2001), 167. ↩︎ - Real Academia Española de la Lengua,Diccionariodelalenguacastellana,3:500. ↩︎

- Entenmann, R. (2016). From White to Yellow: The Japanese in European Racial Thought, 1300–1735, written by Rotem Kowner. Journal of Jesuit Studies, 3(1), 132-134. https://doi.org/10.1163/22141332-00301005-16 ↩︎

- José Gumilla, S. J., El Orinoco ilustrado, introd. and notes Constantino Bayle (Madrid: Aguilar, 1946), 86. ↩︎

- Boxer, C. R. 1963 [1977]. Race Relations in the Portuguese Colonial Empire, 1415-1825.

Oxford: Clarendon Press (Relações Raciais no Império Português. Porto: Afrontamento). ↩︎ - ames, G. 2000. Renascent Empire? The House of Braganza and the Quest for Stability in

Portuguese Monsoon Asia, ca. 1640-1683. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ↩︎ - St.Cyprian Treatise X – On Jealousy and Envy (Between 251-257) https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/050710.htm ↩︎

- Origen, Homilies on Genesis (Hom. XVI), https://archive.org/details/homiliesongenesi0071orig/mode/2up. Follows up with “Not without merit, therefore, does the discolored posterity imitate the ignobility of the race.” ↩︎

- Isidore, Etym. IX, xiv.1. ↩︎

- Ibid, Etym, X, LXXXIV-CCXV ↩︎

- Ibid, Etym. V, iv.1-2. ↩︎

- Ewald Muller, Das Konzil von Vienne, 13-1-1312, seine Quellen und seine, Geschichte, in the Vorreformationsgeschichtliche Forschungen (Miinster, 1934), pp. 99,

Io8, 113-I4. ↩︎ - Bibliotheque nationale MS. Latin, 1450, fol. 62′, quoted by Nod Valois, La France et le grand schisme d’Occident (4 vols., Paris, I896-I902), IV, 283, n. 2 ↩︎

- Historia Francorum 6, in Le “Liber” de Raymond d’Aguilers, ed. J. Hugh and L. L. Hill, introduction ↩︎

- Loomis, L.R. (1939). Nationality at the Council of Constance: An Anglo-French Dispute. The American Historical Review, 44(3), p.508. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1839900. ↩︎

- Discursos dos Embaixadores Portugueses no Concílio de Constança 1416, Pereira, Reina Marisol Troca.- s.l. (2008) ↩︎

Leave a comment